Definitions

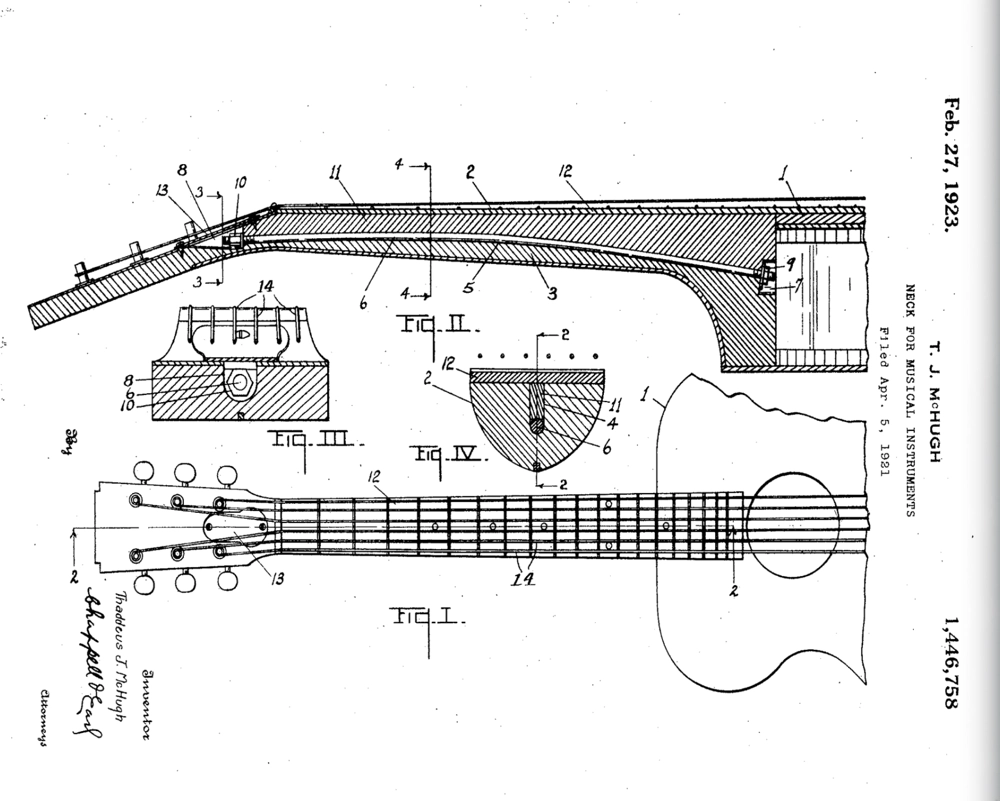

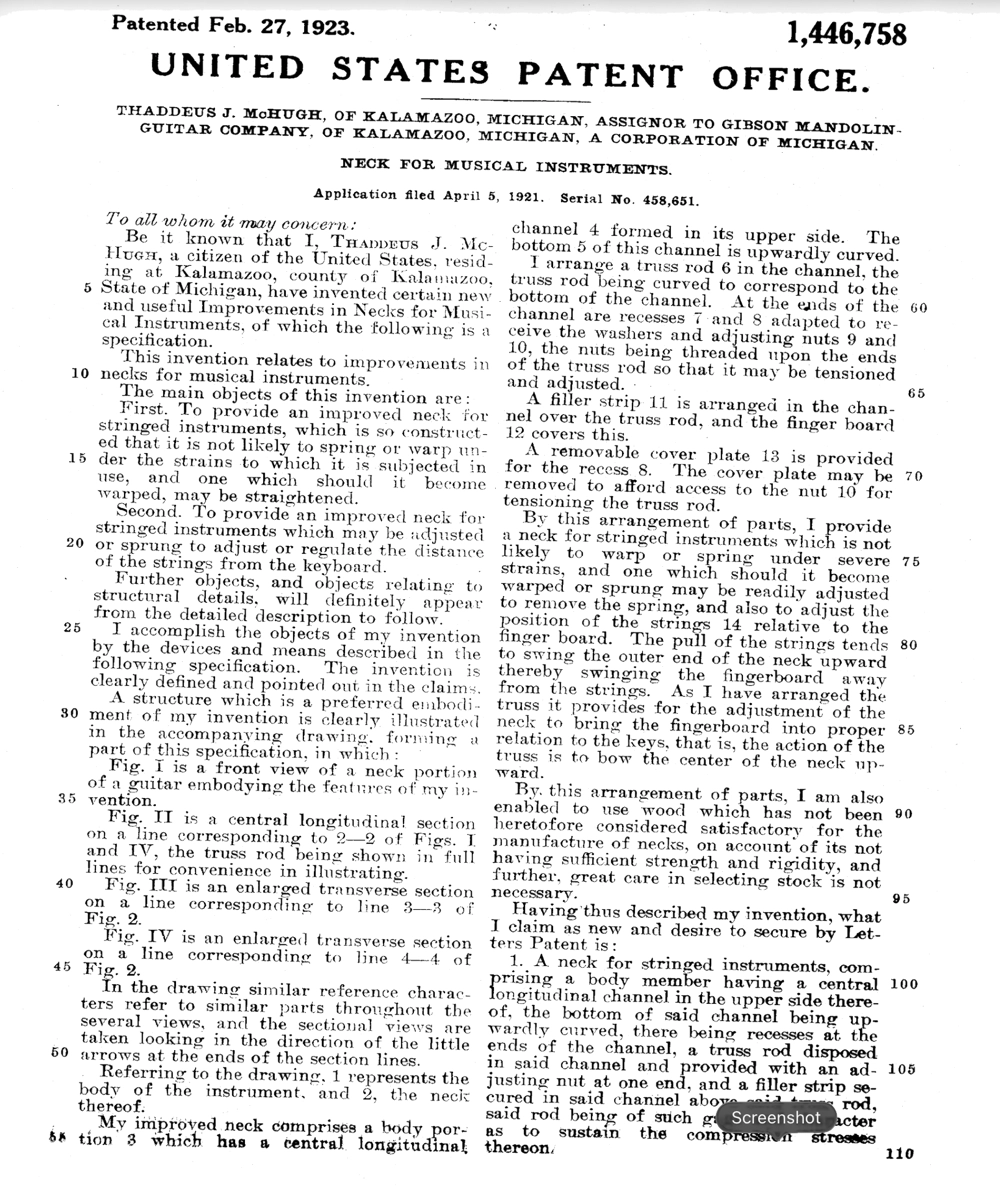

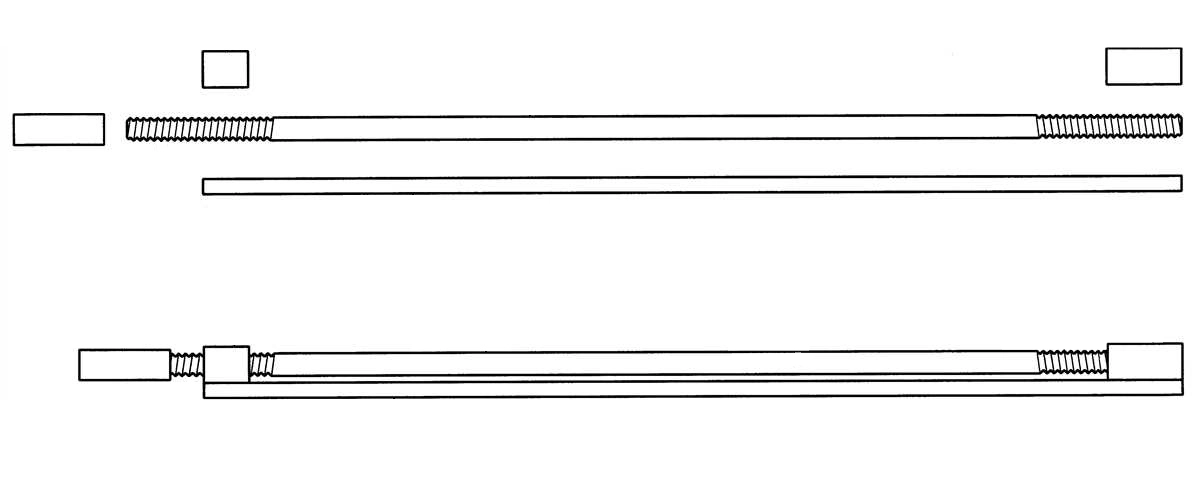

The neck truss (or "truss rod") exists as a solution to a problem. By gaining greater understanding of the problem we may better appreciate the solution.

Action: For the guitarist, "action" refers to the string height above the frets (Action is also measurable on fretless boards, but that is another discussion). Most specifically, action is the distance, as measured at the 12th fret, between the top of the fretwire and the bottom of the string. This distance often varies slightly, string-to-string, as well as fret-to-fret. The radius of the fretboard/fretwire and the radius formed across the strings (as determined by the radii of the nut and the saddle) may or may not be identical. Additionally, a deliberate slope is most often formed in the saddle, independent of its radius, that positions the strings closer on one side of the fretboard (typically the "treble" side) than the other. Action is, therefore, usually provided as two numbers that have been measured at the 12th fret: action at the 6th string, and action at the 1st string.

Relief: An entire section is dedicated to this topic, a little later on in this article. In short, relief is a slight, concave curvature in what would otherwise be a perfectly flat plane across the surface of the frets. Its purpose is to prevent (or mitigate) the incidence of contact of the strings with the frets, primarily for fretted notes. Pragmatically, relief refers to a slight forward bow in the neck that may help to reduce string buzz for extremely low actions on guitars that are otherwise perfectly set up.

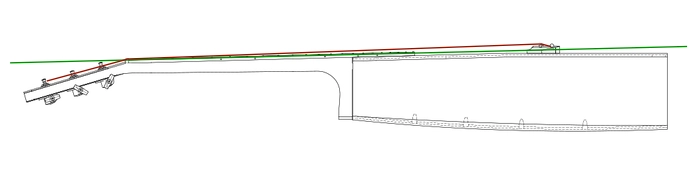

Forward Bow: For most all guitar necks, there exists a tendency of the guitar strings to curl (or "bow") the neck forward. This causes the strings to rise away from the fretboard, raising the action. An elevation view (from the side) of the neck reveals that the bottom of that curve, as viewed across the surface of the fretboard on a neck under string tension, occurs near the 5th, 6th, or 7th frets (depending on the guitar). As the forward bow increases, the action is increased, and the guitar becomes more difficult, if not impossible, to play. There does exist a condition (perhaps more theoretical than actual) where a dead flat, un-bendable neck is pulled forward at the headstock without bowing, but this is due to body flexion (neck block rotation), and is a separate (though related) topic.

Scale Length: The nominal distance from the nut to the bridge. More specifically, the distance from the front edge of the nut, as the string leaves the slot (fret #0) to the 12th fret, multiplied by a factor of 2. If this total distance were to be used in order to determine the precise position of the crest of the saddle, the intonation of the guitar would suffer as the fretted notes would all sound sharp (over-simplified: fretting a note increases the tension of that string, resulting in the note sounding sharp). This is rectified by adding a small, but calculated, distance to the scale length, called "compensation", and using the new total distance to precisely position the saddle. Note that guitars built having longer scale lengths will exhibit increased string tension (when compared to shorter scale lengths having strings tuned to the same pitch), but can provide a "punchier" or "brighter" sound. Short scale guitars are often perceived to be easier to fret, and tend to sound "warmer".

String Tension: String material, gauge, and length determine the measurable force that will be applied to a given guitar as the pitch is raised. Simplified: the tighter the string (the higher the pitch), and/or the larger the gauge, and/or the longer the scale, then the greater the tension. In standard tuning (EADGBE), when tightened to "concert pitch" (A=440Hz), a set of D'Addario EJ16 12-53 Light PhosphorBronze measures 163.27 lbs of combined string tension on a guitar having a 25.5" scale length. Reduce that scale length to 24.9", and that same set of strings will measure 155.68 lbs. of tension. At 24.9" scale length, change the set of strings to D'Addario EJ11 12-53 Light Bronze, and the tension drops to 151.54. A set of Silk & Steel will have lower tension, and a nylon set will have even lower tension.

Neck Stiffness: It may come as a surprise, but overall neck stiffness is not measured in the modern acoustic guitar (if it is, it isn't published). The reason behind this may not be what you think. Read on to learn why.