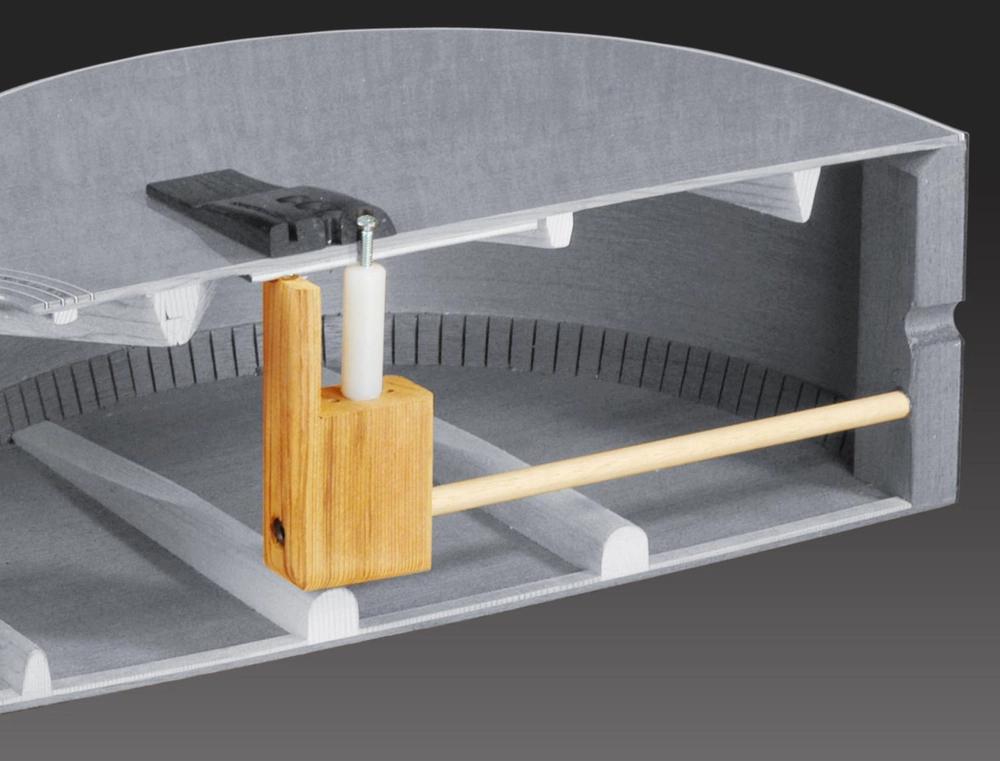

The JLD Bridge Doctor directly addresses the forward rotation of the bridge by applying a less than or equal rotating force in the opposite direction. Leverage is used to pry the bridge back into position, accomplished by first securing a post to the bridge and then pushing a dowel held at a right angle with that post against the tail block. Using my truck tire analogy, bolt a big block of wood to the underside of the platform on which the tire rests. Like the keel of a ship, engineer it to hang 4 ft. below the deck of the 6 ft. platform. Position a jack between the big block of wood and the tree behind the table (the other tree). Expand the jack and make use of leverage to drive the back legs of the platform down to the ground.

Ta da! The principle works. Rotation has been countered. However, do you notice how both the pull of the rope (strings) on the tire (bridge) and the push of the jack (wooden dowel) on the block are forces working in the same direction? With a JLD Bridge Doctor installed, the soundboard directly in front of the bridge is the direct recipient of these forces. A load is applied across the surface of the soundboard between the bridge and the soundhole.

I have also added weight to the equation. This will lower the resonant frequency of the guitar (demonstrated in my test results). Whether this produces pleasing or displeasing results, a change in tone will definitely occur, so plan for it.

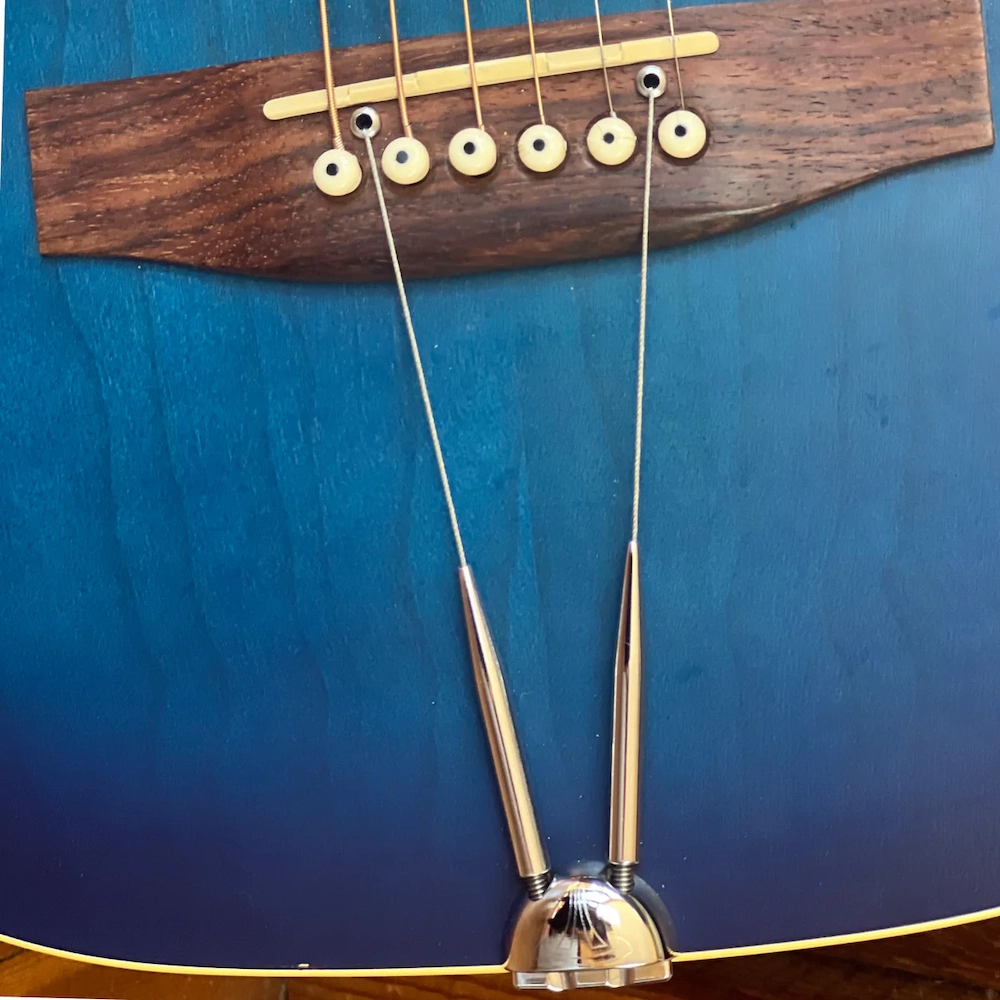

The TurboTail is working the problem differently. Unlike the JLD Bridge Doctor, which is anchoring a lever to the underside of the bridge and literally pushing that lever away from the tail block and toward the headstock, the TurboTail is pulling the bridge toward the tail block, directly countering the pull of the strings in the direction of the headstock. The strings are pulling the bridge forward. The TurboTail is pulling the bridge backward.

Using my truck tire analogy to visualize this, after removing the jack and the big block of wood (the "keel") that was mounted beneath the platform, simply attach a second rope to the tire on the opposite side of the first rope and stretch it to the adjacent tree, the same one we were pushing our jack up against. Wrap it around the tree at a point 5 ft. off the ground and pull that second rope nice and tight. Watch as the back legs of the platform re-connect with the ground. One rope pulls the tire in one direction, and a second rope, attached to the opposite side of the tire, pulls the tire in the opposing direction.

As the tests will show, the JLD Bridge Doctor definitely decreases bridge rotation, but it does so at the expense of also decreasing top deflection. It affixes the soundboard in place. This may or may not prove to be a good thing, but it is how it works. It also increases the load across the surface of the soundboard directly in front of the bridge. Additionally, the JLD Bridge Doctor dramatically lowers the resonant frequency of the soundboard, on which the TurboTail has no measurable effect. See the test results. Or conduct your own.

The TurboTail will also have a nullifying impact on bridge rotation, eliminating it altogether, if so desired. Most importantly (and quite surprisingly), the TurboTail actually increases top deflection and it accomplishes this without altering the resonant frequency of the soundboard. This isn't theory, by the way. I measured these significant factors.