The Infamous Guild Neck Reset

A deep dive into the topic of Guild neck resets, using my own 1976 F-212 XL as an example. Dedicated to Guild owners everywhere ...

A deep dive into the topic of Guild neck resets, using my own 1976 F-212 XL as an example. Dedicated to Guild owners everywhere ...

My 1976 Guild F-212 XL is in need of a neck reset. Guild guitars have taken on legendary reputation for being difficult to disassemble. Let's see if this one lives up to its name. This article is dedicated to the countless Guild acoustic guitar owners whose guitars have desperately needed a neck reset.

For details regarding neck resets, what they are, how to determine if and when they are needed, etc., I encourage you to read my article » Neck Resets.

Let's dig right in to what is going on with this 50-year-old Guild 12-string.

A common practice used to check to see if a neck reset is required is to rest a straightedge across the top of the frets of the fretboard. As the test is presented, if the straightedge just kisses the top of the bridge, as opposed to ploughing down into the soundboard, you are to conclude that no neck reset is required.

However, this straightedge test does not tell us the whole story. Our guitar passes the straightedge test where, instead of falling below the top surface of the bridge, a straightedge laid across the frets makes contact with the top surface of the bridge.

Additionally, it looks like we have plenty of saddle remaining, implying we can just shorten the saddle and the guitar will be fine.

But my guitar is NOT fine. Not only is my guitar, for all intents and purposes, unplayable, but it is currently only capable of producing sub-optimal volume and tone. What factors definitively inform me of my guitar's need for a neck reset?

✅ - My fretboard is a flat as I can make it using the twin compression rods. There is no forward bow in the neck.

✅ - The back of the bridge on this 12 string remains securely glued down to the soundboard, with zero gap. Additionally, all internal bracing is securely fastened in place.

✅ - While some bellying has occurred over time, it is by no means severe.

❌ - My target measurement is 1/2″. This guitar barely measures 3/8", falling a full 1/8" short.

✅ - The nut slots are cut and filed as low as they can go without introducing string buzz. The bottom of the nut slot is at the height of fret 0.

❌ - My target height is no more than 6/64" from the top of the 12th fret to the bottom of the 11th string, the low E.

I am measuring 9/64".

So, why not just lower the saddle?

Lowering the action from 9/64" to 6/64" would require taking 6/64" (3/64" x 2) off the saddle. There is only 8/64" (1/8") remaining. Taking such a step would effectually bury the saddle in the slot. Additionally, it would further reduce the overall string height in front of the bridge. Essentially, if I were to take conventional steps to make this guitar more playable, I would kill what remains of the sound of this guitar.

Without question, I have but one choice before me, and that is to reset the neck of this guitar.

In my experience, the primary culprit behind the need for Guild neck resets is the shifting of the neck block, the worst case scenario resulting in the shearing of the soundboard along the fingerboard extension on one or both sides. The soundboard does NOT have to split along the fingerboard extension for the neck block to have shifted, though it is probably only a matter of time.

You can read all about this topic in my article » Body Flexion - Neck Block Shift and Soundboard Shear.

Thankfully, there is no evidence (yet) of splitting in the soundboard of this particular 12-string, yet, nor has the neck block provided me with any indication of failure.

Guild acoustic guitars, particularly older models, are somewhat legendary among repair shops, the consensus being that neck resets are more difficult to perform on a Guild than on other guitars. The Guild brand is among those who did not switch to bolt-on mortise and tenon necks, choosing to retain the more traditional glued-on compound dovetail joint. To reset a neck, it is first necessary to remove it. Guild necks were first attached to the body, and then the finish was applied. This complicates the removal process and adds the need for touch-up efforts once the neck is re-applied.

I stumbled across a quote from Ireland's Gerry Hayes of Haze Guitars, that cleverly expresses the common sentiment regarding the topic of Guild neck resets:

"Neck resets, therefore, range from relatively-easy (Taylor NT necks), to a-bit-more-hassle (bolt-on necked guitars) to break-out-the-steamer-and-the-tea (Martins), to break-out-the-steamer-and-the-whiskey (Gibsons), to 'oh-god-not-a-bloody-Guild'."

The Finish - To remove the neck, the lacquer “seal” must first be broken. After the neck is reset, that lacquer must then be touched up. This can be complicated by a tinted finish, though it isn't a particular nightmare in and of itself. If, by extreme contrast, you have ever reset a Taylor neck (bolt-on, no lacquer touch-up necessary), you would understand the extra work involved on a Guild neck, along with the additional equipment and skills requirement.

The Glue - If you have reset enough Martin necks you may have run across that occasional instrument where it seems as though you could simply pull the neck off after exhaling a warm sigh across the heel. If you were to then encounter any one of the several Guild necks where any and all open space in the neck joint has been thoroughly flooded with 250 to 300 gram strength hide glue, you would likely conclude that Guild neck resets can be more difficult to remove.

Some Guild necks are more difficult to remove than others, although few, if any of the ones I have encountered from the 1970s and up through 2010 have ever been as easy to remove as the bulk of Martin necks I have removed from the same period. Unfortunately, I cannot provide anyone with an authoritative list of which Guild guitars are more difficult than others, as it remains a mystery even to me until after I have started on a removal.

At issue is the amount of glue applied in the neck joint, and the surfaces to which the glue has been applied. All that should be required of a properly fitted compound dovetail joint is a brush (or fingertip) stroke of glue along the two sides of the tail. The purpose of the adhesive is merely to prevent the tenon from sliding upward in the mortise, the reverse direction from which it was “set.” The one and only possible reason I can think of for applying copious amounts of glue to a dovetail joint, other than ignorance (not knowing any better), is to compensate for a sloppy fit. So, rather than take the time necessary to correct the actual problem, the loose fit, someone just adds more glue to hold the neck in place.

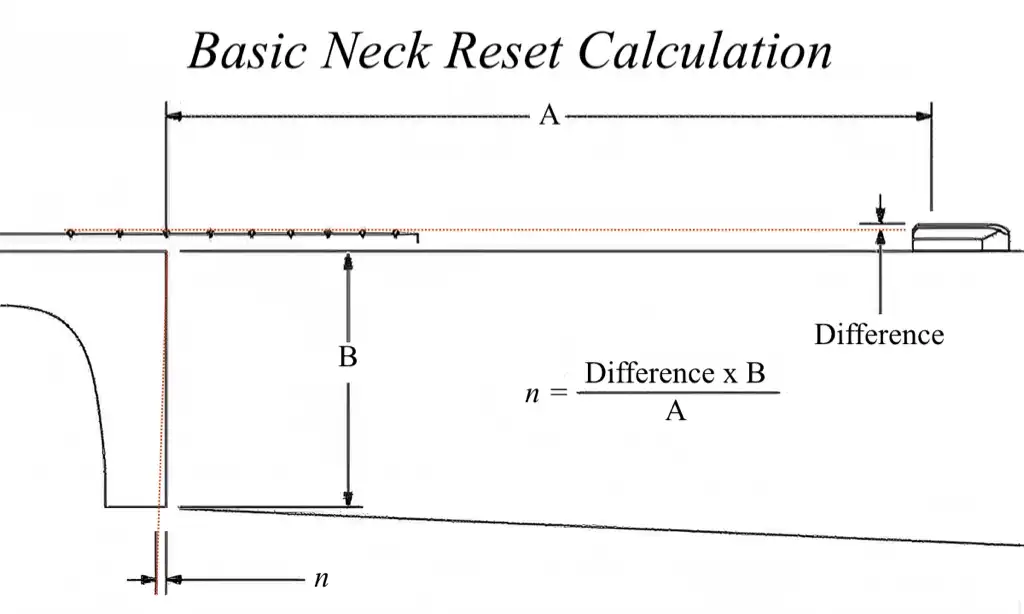

When I am resetting a neck, to determine how to address the neck heel I ignore the existing bridge and make my calculations against my target overall string height. If I can achieve that height using the existing bridge (and typically fashioning a new, taller saddle), great. If not, I make a new bridge.

While this approach is not dissimilar to setting a neck on a brand new guitar, there are additional factors to consider when resetting a neck on an already built guitar, factors that will affect the measurements used to determine how much material to remove from the neck heel. These factors include bellying behind the bridge, sinking in front of the bridge, and shift/collapse at the neck block.

It is advisable to take measurements with the guitar strung to pitch and compare those results with measurements taken after the strings are removed.

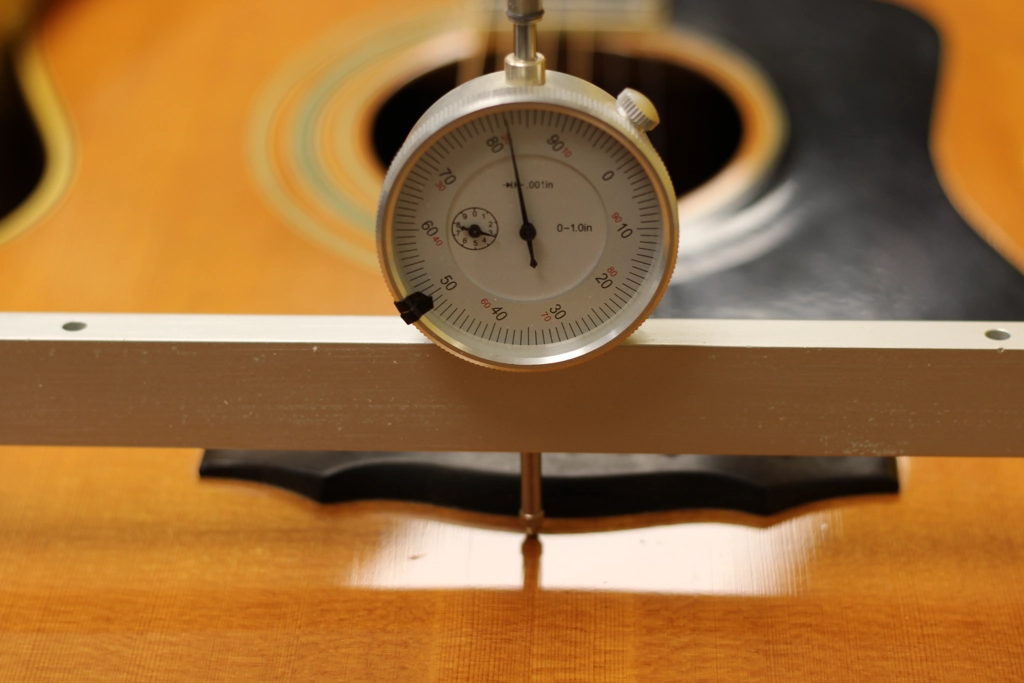

For the soundboard measurements, you can use a dial indicator that references the rims. You can also lay a straightedge across the top and note the deviation from a flat plane.

I did a complete fret job on the guitar, as the frets were original from 1994. I fashioned a bone nut and saddle and strung the guitar, eager to hear the results. The sound did not disappoint, as it was quintessential Guild. I recall walking the instrument out to my wife so she could hear it, and got the nod of approval.

I left the instrument overnight as I planned to buff it out the next day. I almost contacted the owner's sons with the good news, but got busy with something and never called.

That next day I went to retrieve the guitar for buffing and nearly wept when I saw the condition of the soundboard. The bridge was intact, as was the section of the soundboard I had re-glued to the bracing. The problem was that the rest of the soundboard was no longer intact. It had it had nearly completely torn loose from the guitar just behind the bridge! The wood of the soundboard actually sheared off of itself! It was horrifying to behold! At this point the top was obviously ruined.

Check back again.

Break the lacquer seal. Bolt-on or glue-on? Steam? Heat Stick?

Mortise and Tenon, Dovetails and compound angles

Materials, Optimal size

Proper fitting and alignment, glue choices, clamping

Touch-up, drop fill, Re-finish