Assessment 7 - Action Height

Ultimately, action height is a primary contributor to playability. We have seen that string action is determined by a relationship between the fret plane, the nut slot height and the saddle height. The saddle is an independent component that is understood by most to be modifiable in height after the guitar is assembled. If you believe that "as long as a little saddle is remaining above the bridge, all is well", you will most likely be shortening the saddle to lower the action and adjust the string height.

The claim I am about to make should no longer be controversial, but it may rock your world if you are unfamiliar with it:

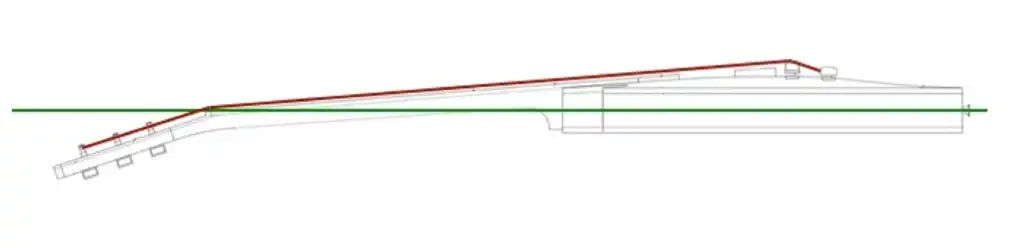

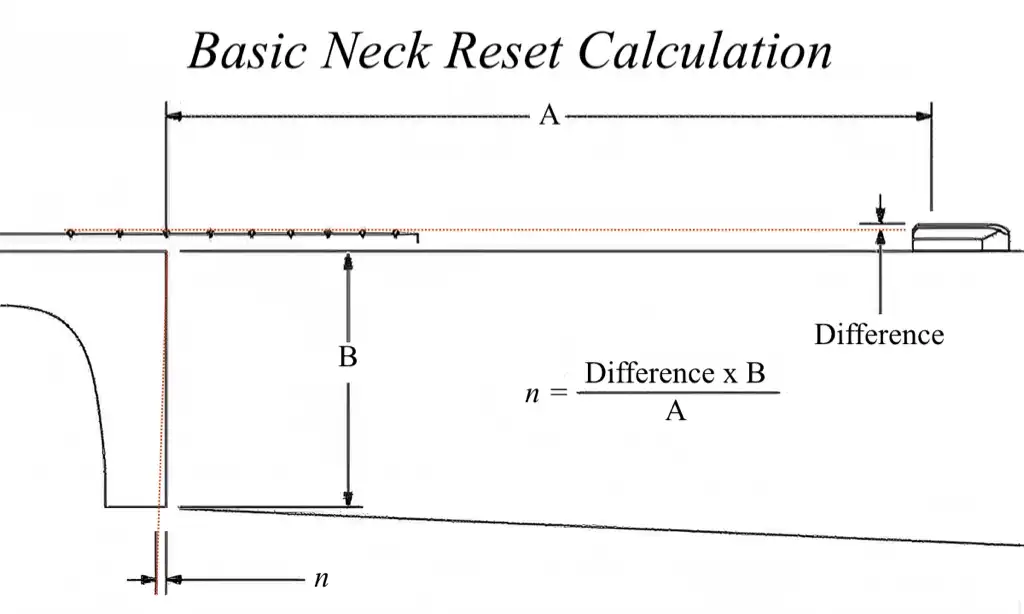

Establishing the string height for player comfort is the primary role of the neck geometry, not the saddle.

Establish the optimal overall string height in front of the bridge, then adjust string action height at the neck joint (Note the benefits of a bolt-on neck).

Sadly, for many builders, overall string height (measured in front of the bridge) was (and remains) an arbitrary measurement. Necks get attached to bodies at some approximate, or "close enough" angle. Bridges are then sized in height to accommodate the string path as determined by the pre-set neck. This may be efficient by factory production standards, but it is backwards, as it is detrimental to the acoustic output of the guitar. The bridge height (bridge and saddle height combination) should be determined, first. Then the neck should be fitted to target that established height.

Maintaining that optimal overall string height at the saddle, slotting the nut to the zero fret depth, and finally setting the neck such that the string path above the fret wire is as low as it can go for your style of playing makes for a perfect setup. If you have achieved that, you do NOT need a neck reset.

If you are new to the guitar, don't really know what "as low as it can go for your style of playing" means, or just like measurements, here are some details:

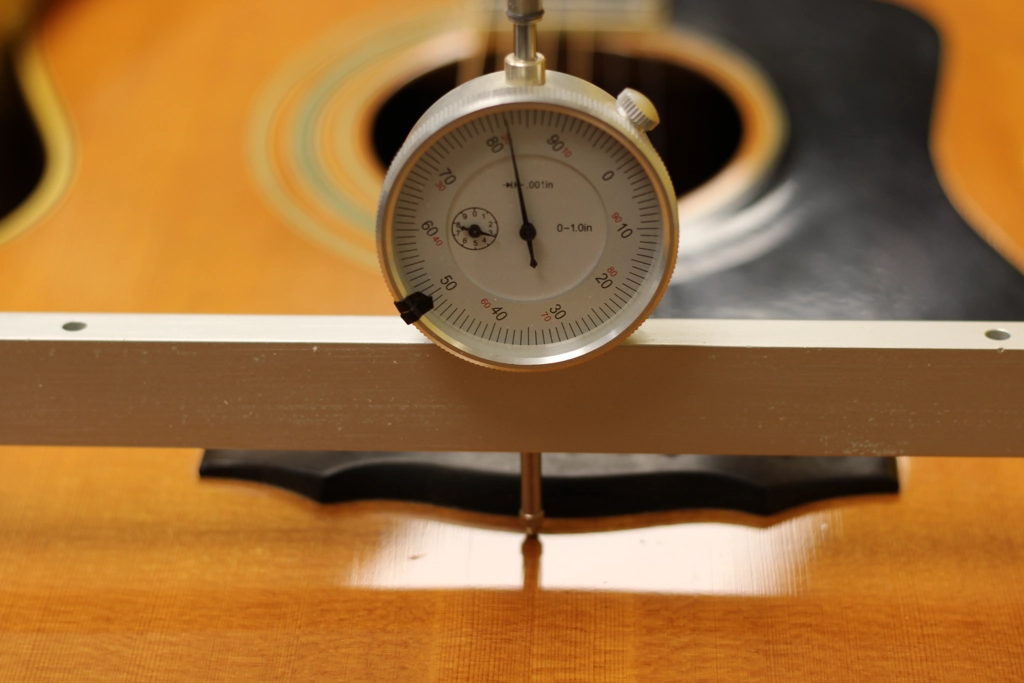

Conduct two (2) measurements, one for the outer-most string on the bass side and one for the treble string on the opposite side. Measure the distance between the bottom of the string and the top of the fret wire beneath it (NOT the fingerboard) at a point halfway between the nut and the saddle. It is typically safe to conduct your measurement at the 12th fret. Measure strings 1 and 4 on a Tenor guitar, or strings 1 and 6 on a 6 string guitar. For a 12 string guitar, measure string 1 and the larger diameter string of the 6th course (typically string 11). Commonly used heights are as follows (fingerstyle players may prefer lower action, aggressive flatpickers may need higher action):

• Bass String: 3/32nds of an inch (6/64ths, 2.4 mm).

• Treble String: 1/16th of an inch (4/64ths, 1.6 mm) - some players prefer 5/64ths of an inch