Manufacturing tuners since 1977, it was in 1983 that Sperzel introduced their revolutionary Trim-Lok design. These innovative tuners made it possible to simply pass the string through the hole in the post, pull it taut, tighten the knob and clip off the excess. Strings now stayed in tune, as the multiple post wraps of yesteryear, which continued to slip as you played, were now a thing of the past. String changing times dropped dramatically. And everybody sought to copy the design.

Four men, namely; Stauffer, Kluson, Grover and Spercel, from three cities, Vienna, Chicago and Cleveland, made these significant contributions to the guitar world over a period of approximately 150 years.

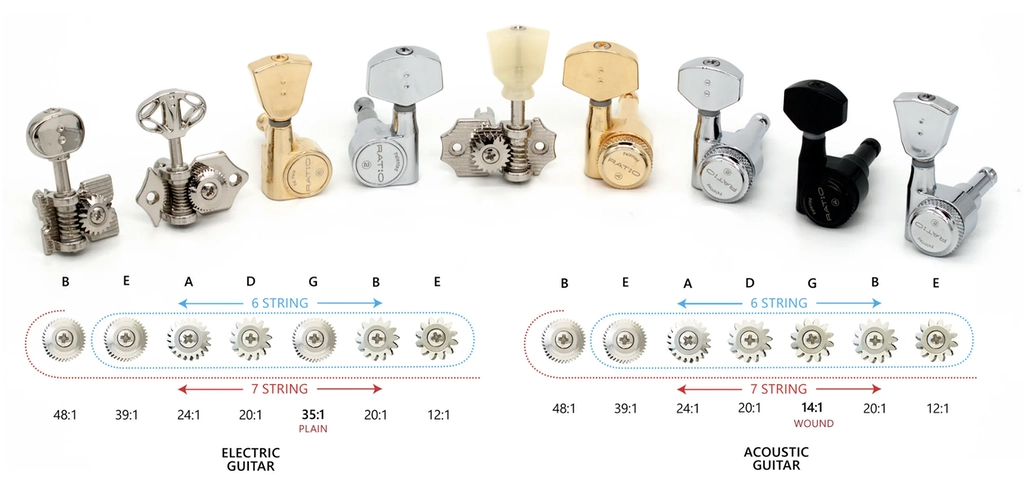

I have used many brands of tuners in my own guitars throughout the years, including Kluson, Grover, Schaller, Waverly, Steinberger, Graph Tech (Ratio), Gotoh, and several others. The tuner I have grown to admire most is the innovative, lightweight and customizable Sperzel Open-Back Trim-Lok tuner.