Most steel string acoustic guitars having wooden bodies are constructed by attaching bent, curved sides to blocks, one positioned at the neck end of the body and the other at the opposite end, or tail. Those sides then receive an additional treatment in the form of two small ledges (called linings) added around the inside perimeter of both the front and the back of the sides. Sides, blocks and linings together form a shell onto which both a front plate (also known as a soundboard or guitar top) and a back plate are glued, completing the body. The guitar neck, constructed independent from the body, is then attached to the body by joining it at the neck block.

This article will explore the details of constructing and applying all three elements, the neck block, the tail block and the linings. I'd like to dedicate the article to Harold F. who inspired its writing. Let's dig in...

Wood is composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin and water. Various species have additional extractives such as oils and resins that color the wood and provide its fragrance, along with varying degrees of rot, insect and fungus resistance. Cellulose, said to be a polymer, makes up about 50% of the composition of wood and is responsible for its strength. Lignin, an amorphous polymer, acts as a binder for the cellulose. It is often described as a matrix in which the cellulose resides, or as the adhesive that glues the wood fibers (cellulose) together. We find more lignin in the softwoods (up to one-third of the composition of the wood) than in the hardwoods, which helps to explain why you can dent Cedar with your thumbnail, and bend or break that same nail on Ebony. The long, thin cellular structure of wood (long in the axial direction, thin in both the radial and tangential directions) is comprised of many layers of microfibrils, bundles of cellulose chains that are coated first in hemicellulose, then in lignin.

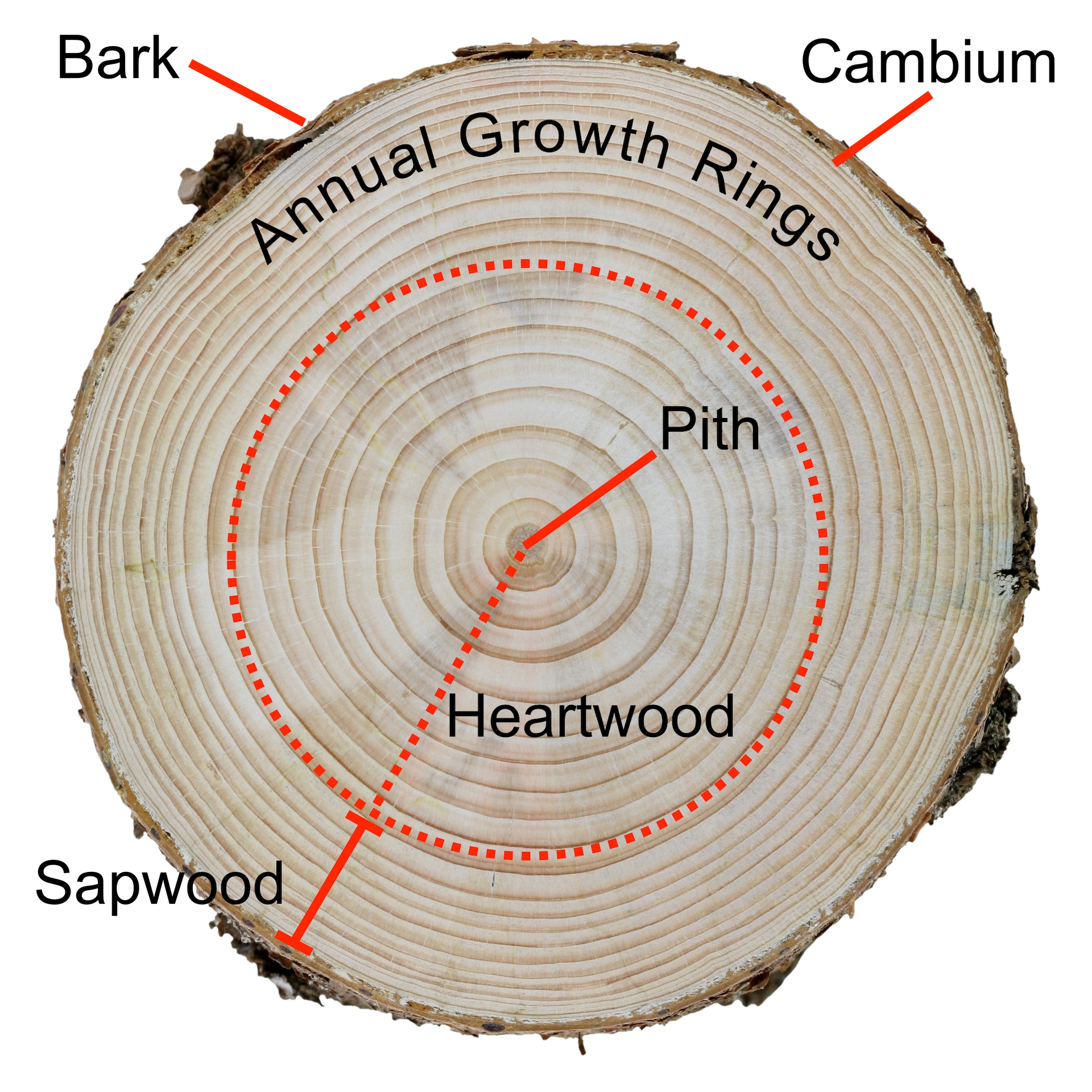

A cross section of a tree, cut perpendicular to its trunk, would reveal four distinct layers:

Layers of a tree

Wood is said to be anisotropic, meaning it has differing strength in different directions. Contrast this with an isotropic metal, which has the same strength in any direction, and you begin to see the role of the grain direction of wood as it relates to the its strength. Wood is significantly stronger along its grain than across it, and some species are significantly weaker across their grain than are others.

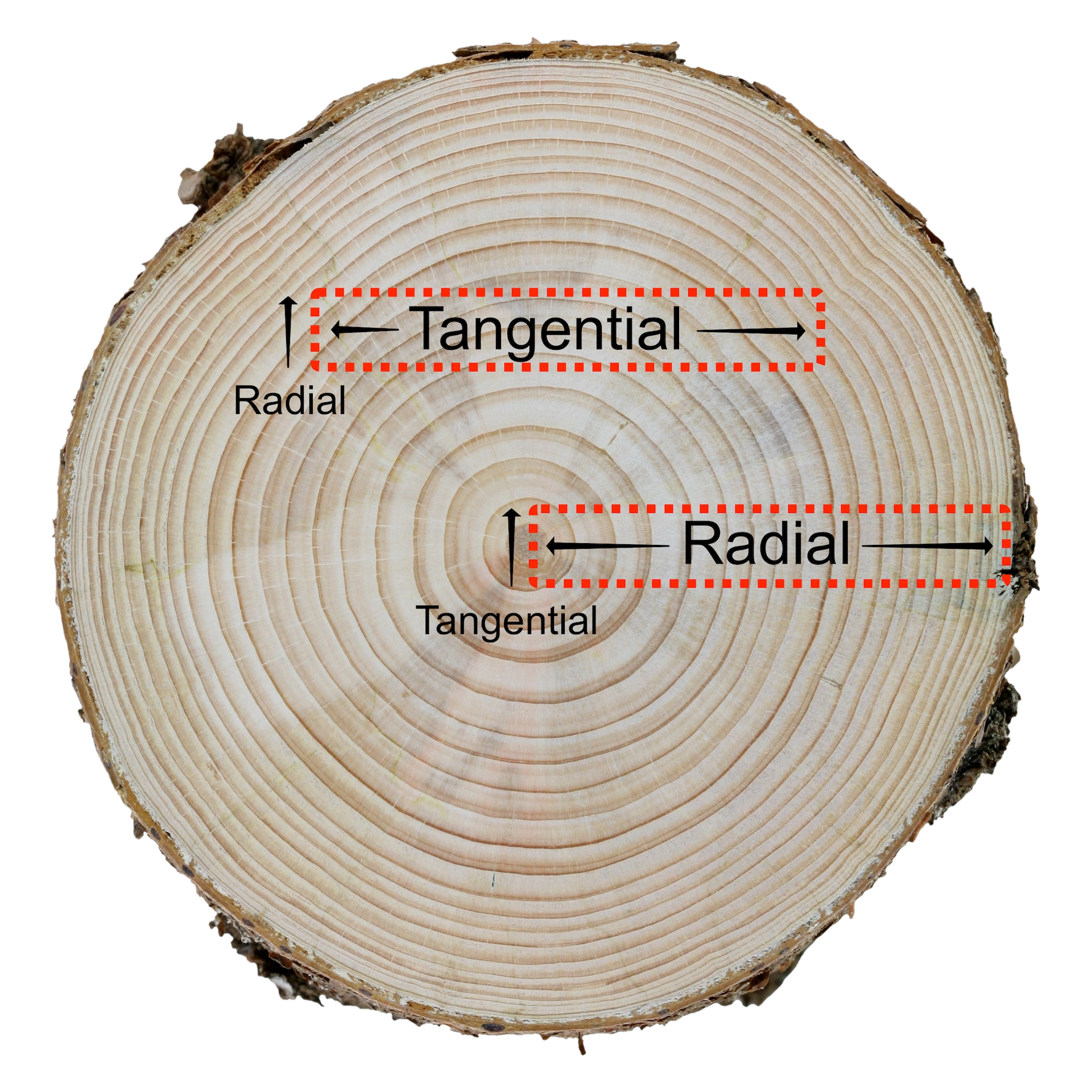

A given board (plank, billet, etc) is said to be strongest longitudinally (axially), along the length of its grain. Boards are typically cut two ways from a log, as referenced against the circular annual growth rings:

How boards are cut

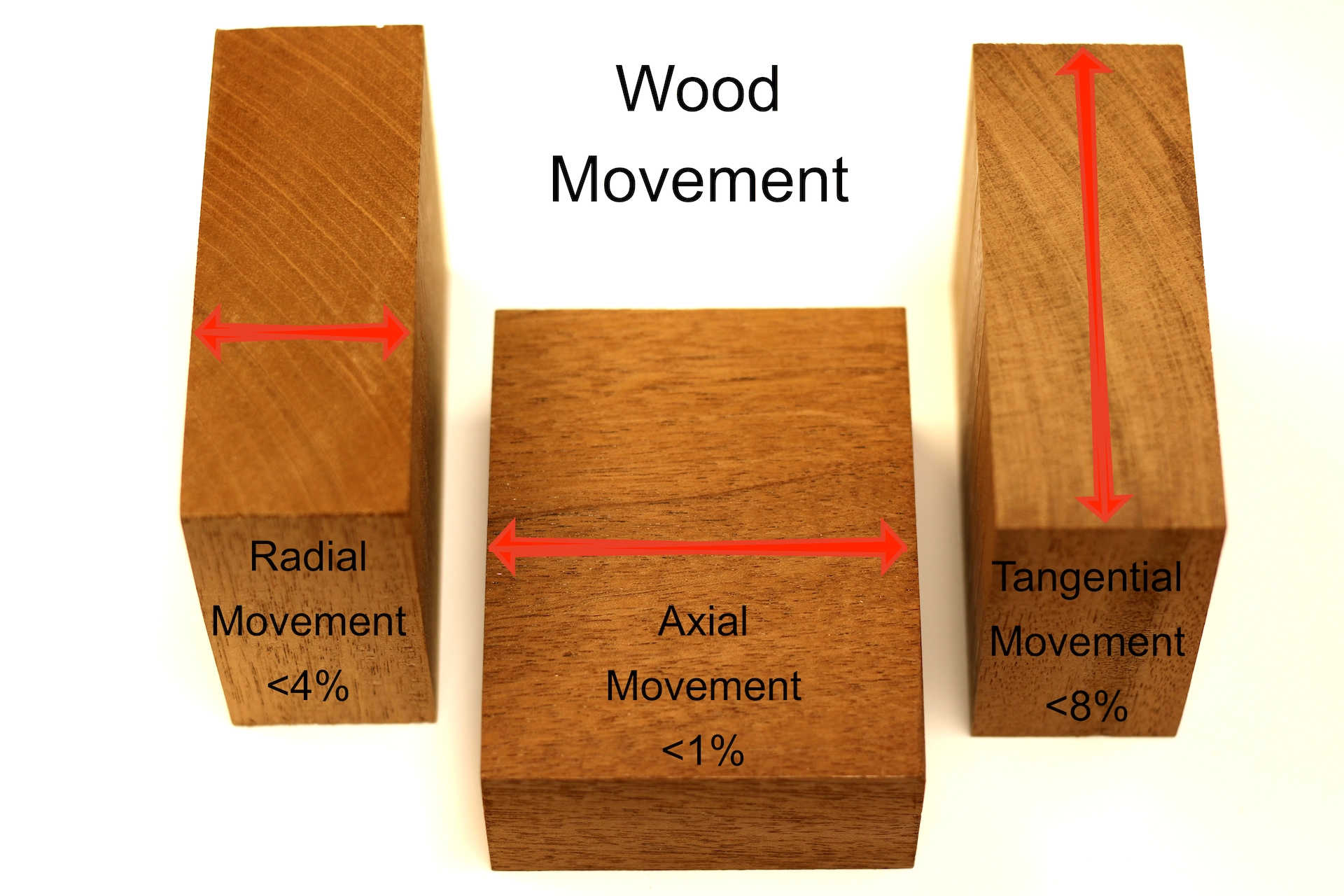

The propensity of wood to expand and contract as it absorbs and releases moisture from its surrounding environment classifies it as a hygroscopic material. Any board cut from any log will be subject to movement occurring along three axes relative to the growth rings of the tree the wood came from. Only two of the three axes, radial and tangential, are of any real concern to luthiers:

Wood Movement

Moisture or, more accurately, the capacity of a given piece of wood to take on and release moisture affects wood movement more than any other factor.

In theory, if one piece of wood was to move at a rate significantly greater than the piece it is glued to, we assume that something would have to give. If the woods are flexible enough, there may be no failure. If not, either the glue joint will fail or worse, there will be cracking or splitting.

Conventional thinking has maintained that, in order to mitigate future splitting, it is critical to align the grain direction of two mating wooden components. Since we have established that any piece of wood is going to move (contract or expand) more across its grain than along its grain, a second piece joined to it should be aligned to move in the same direction.

Countless guitars have been constructed in accordance with this thinking. But is it always the case? The primary wooden components most affected by this thinking are the sides and end blocks. Ironically, the only instruments that are built where these components are of the same species are Mahogany guitars. What are the chances that the end blocks were cut from the same tree as the sides?

Stop long enough to consider: All of these wooden components having been cut from different tress, different species, all having differing moisture content, and thus having differing propensity for movement (movement which, by the way, is miniscule when considering the dimensions we are dealing with)...

End blocks don't crack unless a severe force is applied to them. When the sides split in your {enter favorite vintage guitar model, here}, please note how painstakingly aligned the grain direction of the end blocks were with the sides, and yet the sides split anyway! Which species are more prone to splitting, and why? What was the aged condition of the sides prior to construction (in other words, how far along toward perfectly dried was the wood)? How thin were those sides prior to being finished? These are more significant questions than, "How do I align grain direction of end blocks?"

Wood was once a living tree. Having been cut from the tree, the oils, resins and lignin deep within the walls of the woods cells can take a lifetime to fully dry. During such time, that wood will continue to expand and contract based on its ability to absorb and release the moisture it is exposed to. But once the wood is fully dried and the lignin has crystallized, such wood will no longer take on moisture. Wood that doesn't take on moisture has no moisture to release. Wood that is not taking on or releasing moisture is NOT moving.

This issue of wood movement was of much greater concern back before wood was kiln dried and when glues were entirely dependent on wood mating techniques for bond strength. Modern kilns, torrifaction, laminations and glues such as epoxies can pretty much nullify the argument surrounding the proper alignment of grain direction, if you are willing to participate.

Pre-Mortised Neck Blocks

In addition to providing a surface for the two sides, back and front plates to all join together, the neck block (also known to some as the heel block) serves in the role of housing the neck joint.

There are three common attachment methods whereby a neck may be affixed to an acoustic guitar body.

These methods make use of a mortise and tenon joint, be they straight or dovetailed. The mortise is always cut into the neck block, and this determines the minimum size requirements for this block. Mortise and tenon design plays an additional role, one of alignment. In the case of the compound dovetail neck joint, the fit of the joint determines both it's integrity and alignment.

Less-common attachment methods may exclude a mortise and tenon altogether, and simply hold the neck flush against the body with bolts or glued-on dowels or loose tenons.

Neck blocks are commonly shaped from a quarter sawn or riff sawn solid hardwood rectangular block measuring ≅ 3 x 4 x 1.5 inches (≅ 8 x 10.5 x 4 cm).

For those familiar with USA dimensional lumber: a standard Douglas Fir wall stud has a nominal measurement of 2" x 4" x 8'. The axial (length) measurement is 8 ft (96 inches). The radial (thickness) measurement is 2" (actual: 1.5 inches) and the tangential (width) measurement is 4" (actual: 3.5 inches). For the sake of this example, let's pretend that a 2 x 4 actually measures 2" x 4". If you were to envision setting such a 2 x 4 on a miter or radial arm saw, and making thirty 3 inch cuts, the resulting 30 blocks might provide a mental picture of how commonly used Mahogany neck blocks are cut.

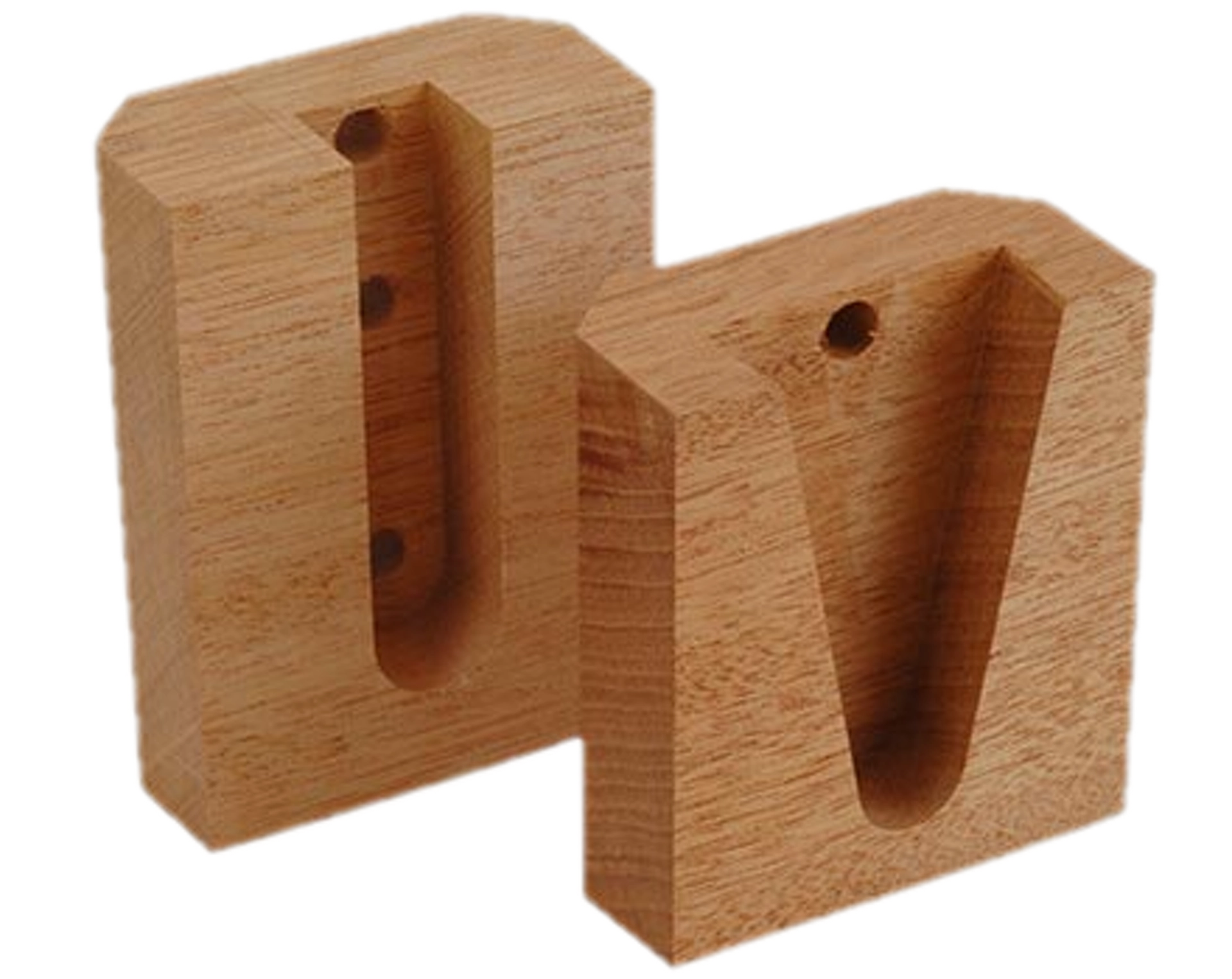

Neck Blocks

Some builders add a step or ledge to the soundboard end of the neck block. This is done to accommodate additional features such as a bolted-down fingerboard extension, or to provide support for what is thought to be the downward pressure on the soundboard beneath the fingerboard extension due to neck rotation.

For more detail on the issue of neck rotation, see my article titled, Neck Block Shift.

Martin Neck Block

Still others will incorporate both a ledge on the soundboard end and a foot that extends further out onto the back plate. These may be assembled from separate pieces of wood (in an attempt to try to match grain directions) or shaped from a single block, be it solid or laminated.

Yamaha Neck Block

Many (most) acoustic guitars feature a thin, rectangular Mahogany tail block, measuring approximately

X

X

I begin with a rectangular block cut from Spanish Cedar. I first slice it lengthwise into three pieces. I cut the center slice in half, rotate both pieces 180°, cut a lap joint into them, and sandwich those pieces between the first and third slices.

In order to successfully attach a back or front plate to the sides of an acoustic guitar, a supporting ledge must first be added to the guitar sides to rest those plates on. With modern epoxies, one could force a connection between the back or soundboard and the thin edge of the sides. However, the moment you cut into that sharp edge to add protective and decorative binding, you would sever the connection. Leaving the side material thick enough to survive the addition of binding would produce a very heavy instrument; that is *if* you could even bend such thick wood.

The earliest practical approach to solving the plates-to-sides attachment issue is seen in the Spanish tentallones, small rectangular or triangular pieces of wood painstakingly glued into place right next to one another all around the inside edges of the body. The guitar can then be assembled with confidence, and works very well for gut and nylon string guitars, as is evidenced by the myriad Spanish-style guitars built using this approach over the centuries. While providing ample support for the plate joinery, tentallones do very little to prevent the body from flexing. This is of significant concern when steel strings are in use.

Tentallones

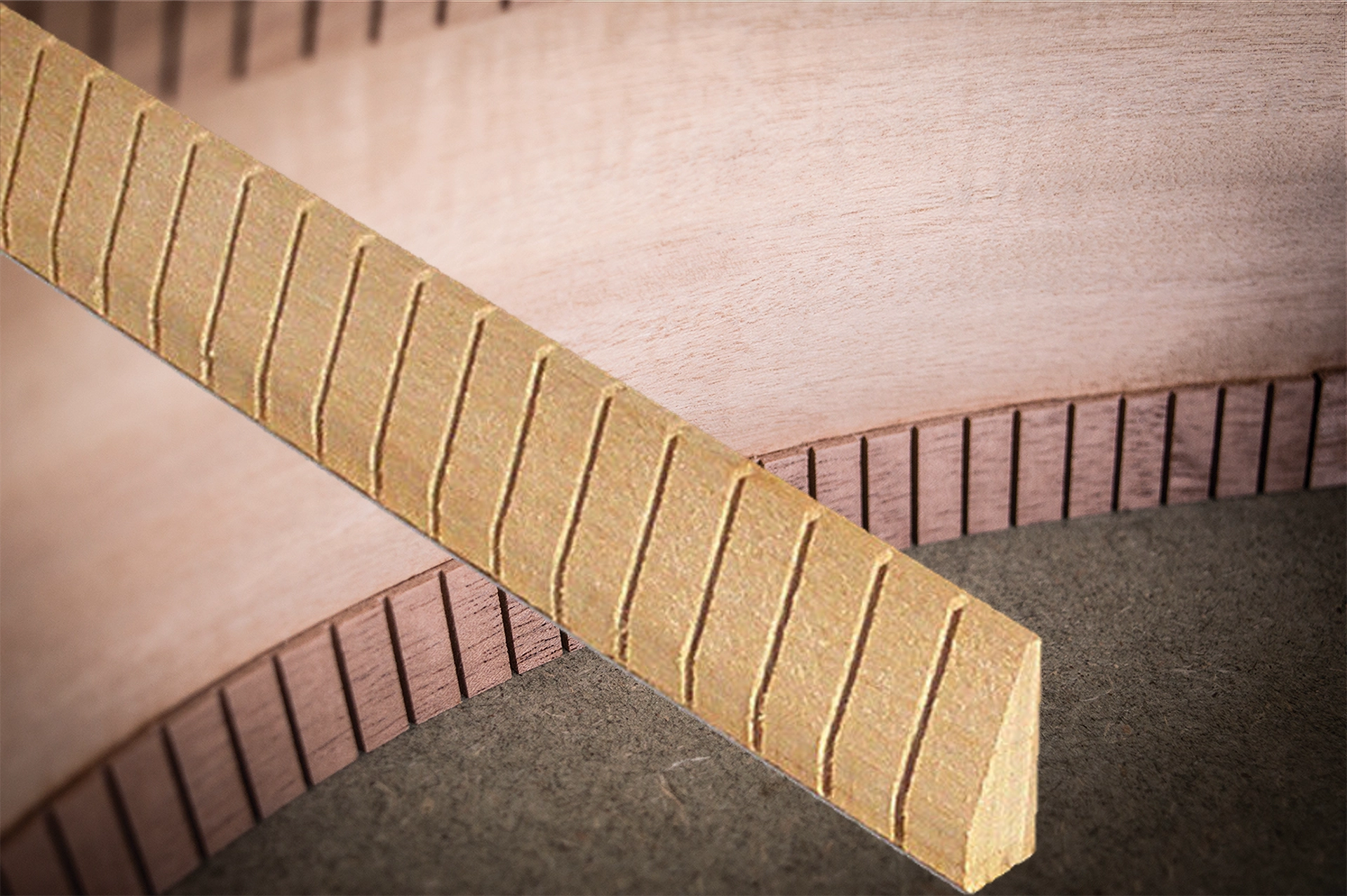

Whether it was to add increased rigidity, or to speed up the installation process, or both, some clever soul introduced kerfing, also called kerfed lining, or linings. Beginning with a thin, rectangular or triangular-shaped strip of wood, such as Mahogany or Basswood, thin perpendicular slits, known as "saw kerfs" are cut into the wood using equidistant spacing. Those thin kerfs do not quite go all the way through the wood, resulting in a very flexible wooden strip. Installation results in an appearance that closely resembles tentallones.

Kerfing

So-called "reverse kerfed linings" are not triangular, and the kerfs are placed up against the sides where they all but disappear from sight. In addition to a cleaner visual appearance, reverse kerfing is much easier to install. More significantly, this style of lining adds measurably more rigidity to the sides than does standard kerfing, resulting in even greater sustain. The more rigid the sides become, the less energy is lost in damping. Many (most) acoustic guitars are built using triangular kerfed lining, with more and more builders preferring reverse kerfed lining. Some makers still use tentallones.

Reverse Kerfing

Having constructed guitars for many years using all three styles of linings, mentioned above, I came to prefer a different approach, that of solid linings, also called "rigid rims". I begin with thin strips of Spanish Cedar, and laminate them into a very rigid rim onto which both the front and back plates can then be glued. They can be laminated straight and then bent into shape, or laminated in a form such that once the glue dries or cures, they need only be installed. The first technique is very practical for the builder having many body shapes and sizes, as constructing multiple forms can become its own career path. Laminating in place (to a form) has a speed advantage (it takes the same amount of time to glue up an straight board as it does a shaped one, and you don't have the additional time requirement of bending the already shaped lamination). This approach also benefits from zero springback, and a perfect fit.

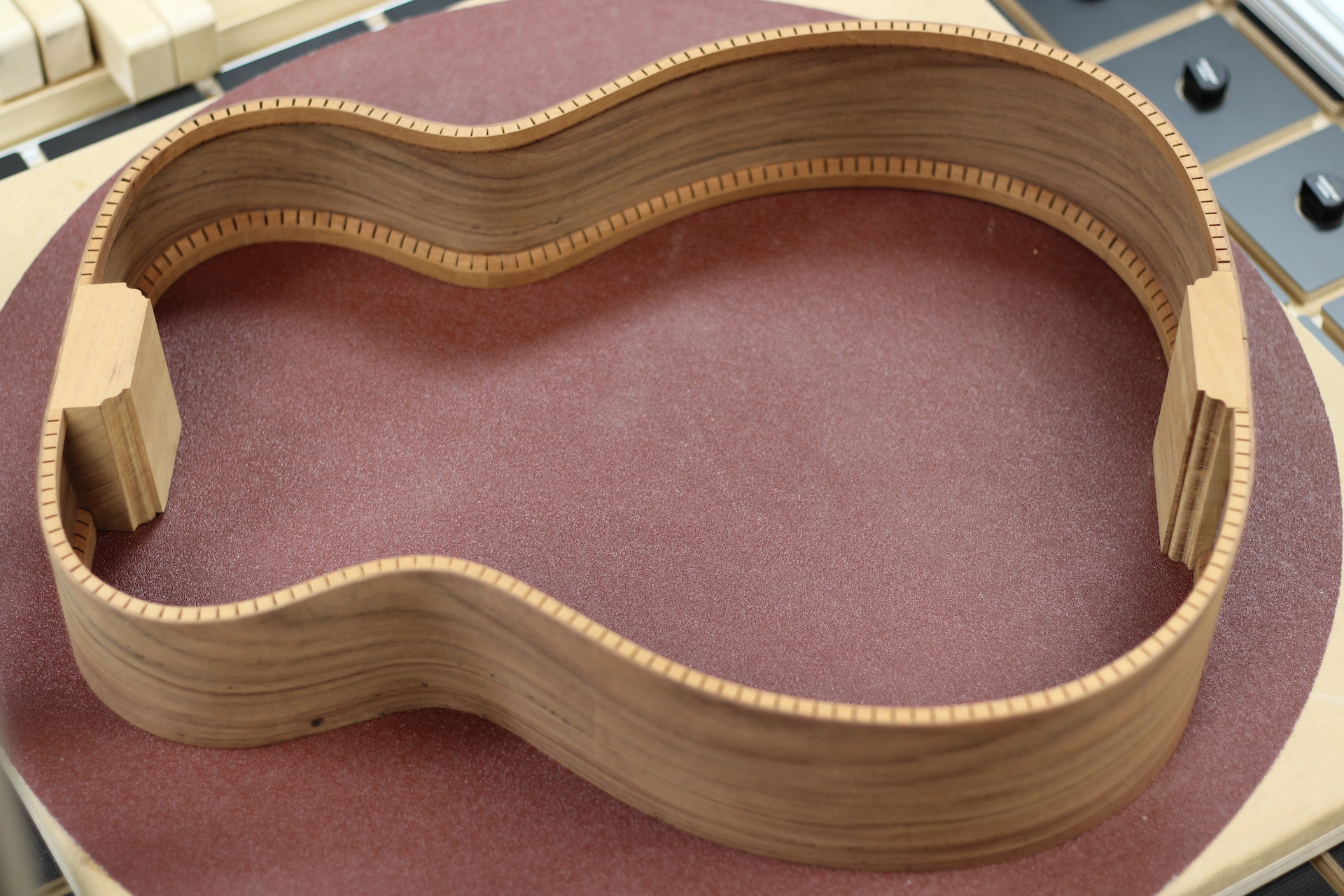

Solid Linings

ccc

ccc