Statue of David

Does a given item have intrinsic worth just because it's "hand-made"? I believe so, as do many others, as evidenced by the number of children's crayon drawings taped, pinned, or held with magnets onto walls and refrigerators throughout the Earth. And we have yet to see 3-D printed violins selling for $20 Million dollars.

When it comes to guitars, significant instruments have been made by the hands of craftsmen who are under the employ of production factories. Does that mean all factory-produced instruments are better than "one-off" or "homemade" or small shop instruments?

I don't own a guitar factory, nor do I have any plans to do so. I do not work in a guitar factory and I never have (though I have visited a few). I have, however, owned many handcrafted and factory-built guitars, and have performed with and/or played and/or worked on several hundred more of each over the last four and a half decades. A couple of my favorite personal guitars happen to be factory-built.

I began playing the guitar as a child, started repairing and building as a teenager, have apprenticed with master luthiers and now, 40+ years after beginning, I have convinced myself I am qualified to offer yet one more opinion on this topic. 😊

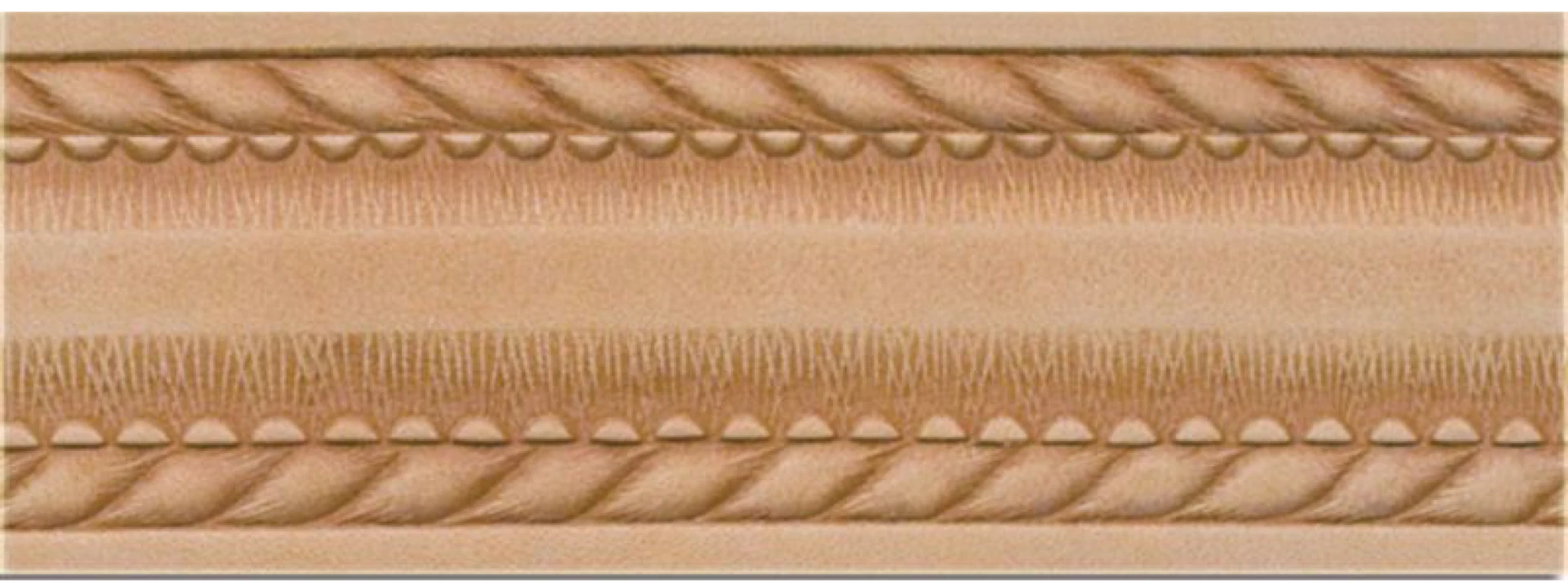

When thinking about the difference between a handcrafted guitar and a factory-built guitar, consider the following contrasts:

One of my own hand-tooled leather belts

A factory embossed belt blank

The chef-prepared meal vs. microwave dinner contrast may be a bit harsh, but I am intending to point out the distinction between examples of custom made and run-of-the-mill, factory-produced items. While a chef is certainly capable of producing a boring plate, his or her reputation and career hinges on such missteps, and it won’t happen often. It is just as unlikely that any diners will be raving over their next microwave meal, their eyes rolling back in their heads, their senses overwhelmed with gastronomic delight, overheard uttering adjectives such as ambrosial, gustatory, brackish, dulcet and sapid!

Factory products are largely governed by owner/shareholder profit and benefit from close monitoring of factors such as market share, executive management, purchasing power, economies of scale, advertising and marketing, labor force, equipment maintenance, repeatability, compliance with safety standards, etc. Much like “spec” homes, factory-built guitars need to sell into a mass market in order to realize a profit and decisions are made, for better or worse, to ensure that happens. To think that all these business issues have nothing but positive impact on the end product would be a bit naïve. It would be just as silly to claim that a factory could never put out a worthy musical instrument. They can. They have. They do.

Independent shop products are largely governed and/or driven by the owner’s economic survival, knowledge and skill level, passion, drive, determination, ingenuity, morality, etc. More like a custom homebuilder than a large spec house developer, the lone guitar maker typically exhibits a greater attention to detail and has more freedom to pursue product personalization than does the factory. Of course, he or she can never compete with the volume of instruments produced by a factory, and is hard-pressed to produce instruments with the same level of consistency.

That is not to say that all factory-made products are somehow inferior, or that any and every small shop’s products are always preferable. Personally, I do not believe that all independently built guitars are better than all factory-made ones (though I secretly want to believe they could be). Yet there are differences between the two and, sometimes, those differences can be significant.

A successful factory excels at repeatability. So-called Quality Assurance/Quality Control monitors standards that have been established to be the factors that are replicated, over and over. The intention is to ensure consistent output and, if that output has been determined to be profitable, another success story can be heralded. Each machine or machine operator has their independent task to perform and, barring any labor force interruption or tool mishap, the whole process or product comes together with amazingly identical precision. Of course, this is exactly where consistency in the production process may potentially falter. Employees move up, on or out and must be replaced and retrained. Knowledge and skill may or may not survive the transition. Machines change and (hopefully) improve and tools constantly wear, so adjustments must be made and deviations accounted for. Or not.

Imagine a large machine, akin to the prototype built by the toymaker’s apprentice in Disney’s delightful rendering of Babes in Toyland, into which stacks of wood are repeatedly fed and out of which emerge popular guitar models.

Babes in Toyland Toy Machine

It is rare to find an independent guitar builder who produces a single product, and even more rare to find one who uses the exact same wood and precisely the same processes throughout the entirety of their career. Multiple models created from multiple species of wood using a variety of tools and techniques over decades make for a rather well-rounded luthier. The very nature of the dedicated craftsman drives him or her to improve and perfect lutherie skills, to master and keep mastering oneself and one’s craft. Over time, the knowledge acquired and the skills mastered are quite extensive, as they must be, for every aspect of every guitar has to be addressed by one person. The master luthier can be counted on to produce a consistently masterful guitar, regardless of the changes in materials, tools, processes or product.

A production guitar factory will most certainly approach craftsmanship, quality and value differently from an independent luthier. All luthiers are not at the same level of knowledge and expertise, just as all factories do not contain identical equipment with identical workforces and policies. For the factory, craftsmanship will often be equated with machine operator skills. Where handwork may be involved, there is a belief that highest and best use will yield greater efficiency which directly translates into profit, so the factory worker will be relegated to reproduce a component or step repeatedly, day after day, likely until such time that he or she can be replaced by a machine or automated process. Quality is usually defined and measured as a target standard for consistent output. Value is typically determined to be more about brand recognition and public perception than the actual time cost of ownership of the instrument.

The skilled independent instrument maker has learned that the response of a given instrument is controlled by ever-so-subtle variations in the thickness of the woods used, the bracing pattern and shaping, the precise sizing of the sound chamber (the body of the guitar), its soundhole/soundport, overall weight, neck and fingerboard choices, surface preparation and finish, etc. This knowledge is used to tailor each guitar to its new owner’s needs and desires. The recipient of such a creation couldn’t care less about how efficiently some shop ran that week. He wants his new guitar to be the best of the best, and his expectations are exceedingly high. This is a glimpse into what craftsmanship and quality can mean to the independent luthier. Value is much more closely coupled to actual costs of materials and level of expertise, and worth (or price) is determined on an individual, case-by-case basis.

There are myriad combinations of construction techniques and even more adjustments and tweaks that the luthier can draw upon to address individual need. Having the knowledge to do so, let alone the flexibility and freedom, is tantamount to success for the hand-maker. No factory (that I am aware of) is in a position to devote such time and attention to an individual instrument.

“Why does one particular guitar that has been built with CNC precision to be just like all the others in a given production run dare to be different?”

So long as the machinery is running smoothly, marketing is properly inciting customer demand, and the accounts are in the black, the company is deemed to be successful. I have speculated for years (and have yet to be proved wrong) that this assembly line approach demonstrates another fundamental principle regarding the intrinsic nature and distinction of wood. With dozens, or hundreds, or even thousands of guitars emerging from a production process that replicates itself to exacting standards, the question persists: how is it that one guitar in n-number of guitars will stand out from the rest of the production batch? Why does one particular guitar that has been built with CNC precision to be just like all the others in a given production run dare to be different, even exceptional at times? As all other factors are identical, one is forced to acknowledge the wood, alone, must be responsible for the difference. Unlike metal or plastic, wood is a living substance having incredibly diverse characteristics that benefit from individual consideration.

The extra attention and accompanying expertise required to coax the maximum musicality out of each and every instrument built, not just the one or two outstanding accidents or close approximations, lies at the very foundation of the handcrafted instrument maker’s business and reputation. At the factory, even if someone were to notice an occasional exceptional instrument amongst a production run, the very effort of pausing to observe the hiccup would be deemed a distraction from the process. That process cannot accommodate variations in the wood (at least, to my knowledge, it hasn’t yet). I consider the ability of the independent luthier to bring all his or her knowledge and skill to bear on the one instrument being built at the moment to be the primary reason why so many independent luthiers’ guitars are easily on a par with or well exceed the very top-tier offerings of the factory-made instruments.

As guitar manufacturing companies grew larger, their respective corporate policies were adjusted in support of the maxim, "We (Production shops) are in business to sell product, not repair warranty claims." Many (not all) guitars were subsequently built heavier, the idea being that a more sturdy instrument will likely endure greater mishandling.

The attention to detail that would result in a finer, yet perhaps more delicate instrument was once held to be a common and desired trait among skilled instrument makers. By relegating that extra attention to detail to a corporate interest’s “Custom Shop,” and employing more generalized building techniques on the assembly line, more standard production guitars could be produced in the same amount of time, potentially generating higher revenue.

As a result of the focus on "lowest common denominator", "one size fits all", and "built to be abused", the market is flooded with shiny products offering mediocre performance. Expectations are dramatically altered among the consumer base, where guitars must now be offered in my favorite color and only cost the equivalent of what I might pay for a new lawnmower.

Not wishing to be remembered merely as the critic who only cast aspersions on the veracity of production guitar factories, I must acknowledge the positive contribution(s) the factories have made and consider the prospects they hold for the future. Much of the design and sound of the modern acoustic guitar is owed to a handful of factory workers who pioneered the field. The rash of independent guitar makers that broke out in the 1970’s built on the foundation laid by those pioneers. Factories came and went (overseas, mostly), and the ones who stayed changed with the times. Some, having the funding, connections and overall wherewithal, had (and have) the potential to research and develop the field of guitar making, and have introduced innovations that benefit us all. Huge efforts have been made in the areas of forestry and conservation, as well as importing and exporting of raw materials. Looking forward, methodologies can be perfected, boundaries can be expanded, myths can be busted, new materials and processes can be explored. That is not to say that all of this will happen or that the end result will be preferable, but it opens up all kinds of possibilities.

So what of the fate of the independent luthier, the lone handcrafted guitar maker? He or she can choose to stay the course just for the love of it, or perhaps incorporate factory machinery or processes into his or her own craft, or choose to apprentice the next generation of independent builders. Or maybe even write a compelling story, retain the movie rights and finally get away from all the sawdust.